As with a few other countries, I had a bit of a head start with Sudan. Over the last few years I’ve read a few books set in Sudan before South Sudan’s independence – then the biggest country in Africa. A couple of these have been written by or about the ‘lost boys’. These were boys who had been caught up, mainly in the south, in a long and vicious civil war. Many were child soldiers, forced by warring parties to join a brutal army, carry guns and join the ‘war’. Some of the stories are quite unbelievable – escaping to find refuge – in the meantime joining a large refugee trek across dangerous landscapes fighting both hunger and lions.

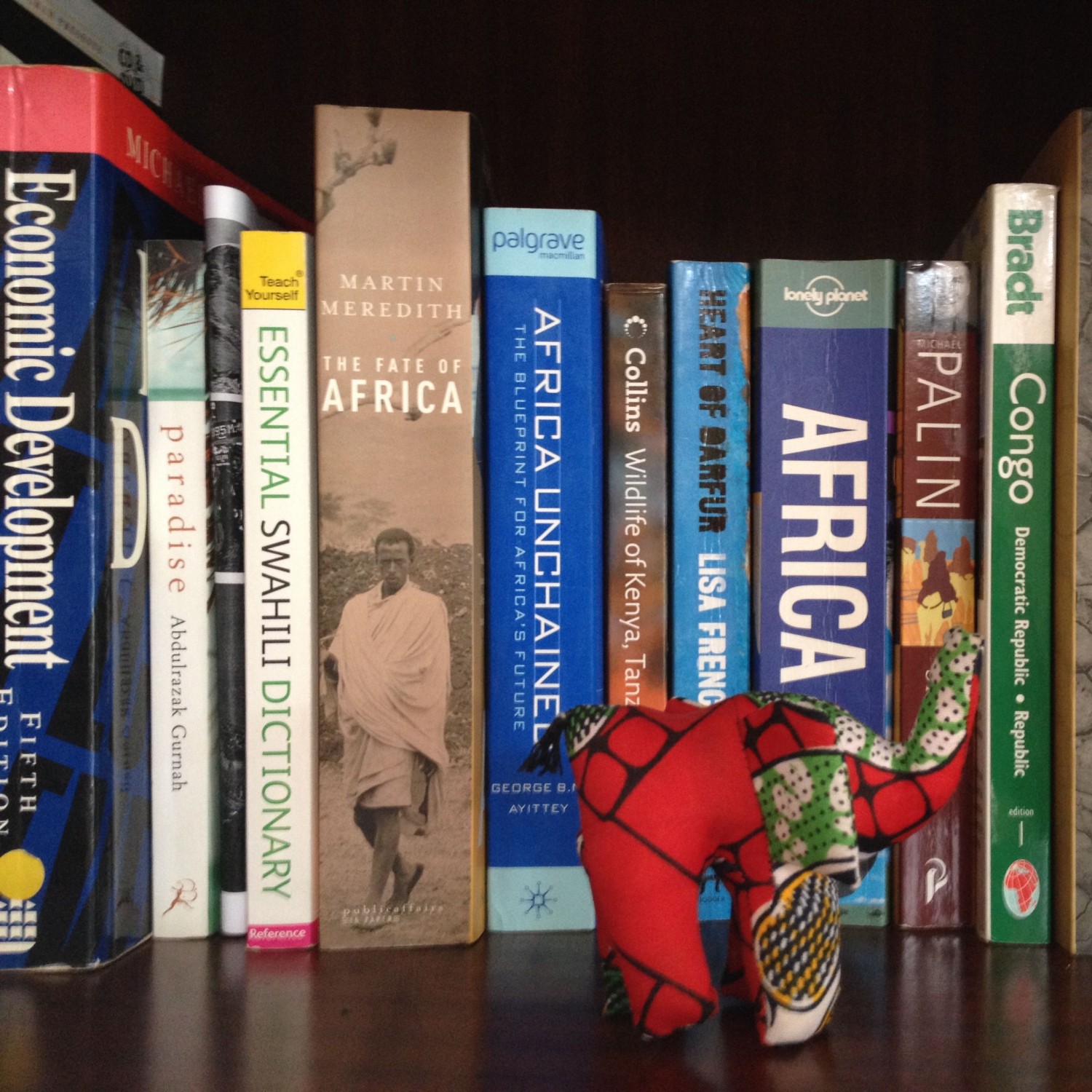

Sudan (and now South Sudan which I will cover separately) has faced a long history over the last few centuries of protracted and separate civil wars in its ‘peripheries’. What is now South Sudan, the southern border areas of South Sudan (South Kordofan, Blue Nile state, Abyei), parts of eastern Sudan, and Darfur. In endeavouring to learn a little more about one of these areas and to get a bit of a better sense about what it might be like to work in the depths of a humanitarian operation I read the account of a Medicines San Frontiers (MSF) nurse in Darfur. Heart of Darfur by Lisa French Blaker gave me a decent account of both. Darfur is the area of Sudan that borders the country of Chad. An area the size of France, it is a lawless place of rebels and desert ruled by ‘sultans’. Darfur is another long-standing conflict of Africa that most recently has become increasingly more violent for the local population. Over 190,000 people have been displaced since February 2014.

Sudan (and now South Sudan which I will cover separately) has faced a long history over the last few centuries of protracted and separate civil wars in its ‘peripheries’. What is now South Sudan, the southern border areas of South Sudan (South Kordofan, Blue Nile state, Abyei), parts of eastern Sudan, and Darfur. In endeavouring to learn a little more about one of these areas and to get a bit of a better sense about what it might be like to work in the depths of a humanitarian operation I read the account of a Medicines San Frontiers (MSF) nurse in Darfur. Heart of Darfur by Lisa French Blaker gave me a decent account of both. Darfur is the area of Sudan that borders the country of Chad. An area the size of France, it is a lawless place of rebels and desert ruled by ‘sultans’. Darfur is another long-standing conflict of Africa that most recently has become increasingly more violent for the local population. Over 190,000 people have been displaced since February 2014.

Heart of Darfur offers little in the way of hope that the conflict in Darfur will finish anytime soon. But reading about the people who chose to work in this difficult environment, and the people who are living the war can’t but help make you reflect on what’s going on in this world, and what people choose to do with their lives. That people shot, sick, or in need of medical assistance would walk days through desert to try and find help. That those that help have to negotiate military and officials to get to reach those in need, risk getting caught in cross fire, and themselves live in often difficult and trying circumstances. It is definitely another world from the relative comfort of many of us.

The other Sundanese book that I read was a little less heavy in terms of subject matter. Tayeb Salih’s Season of Migration to the North was recommended by an Egyptian friend of mine. Season is described as the ‘classic post-colonial Sudanese novel’. Published in 1966 it’s not a long novel, but the style and language used in writing is both rich and poetic making it the type of book that for many people (like me) need to employ a strong degree of concentration. Essentially it’s about a Sudanese man, who leaves his northern Sudanese village for Europe to study. While there he leaves a trail of broken hearted western women lovers, many whom have committed suicide when left for his next conquest. He returns to his village.

Upon returning to his village, he becomes preoccupied with Mustafa Sa’eed, a man who moved to the village while he was away. It is suggested that he marry Se’eed’s widow. Someone he seems attracted to, she seems to take a pragmatic approach to the proposed arrangement, but it’s something nonetheless that he initially rebukes and seems to feel obligated not to reverse his decision.

“The world has turned suddenly upside down. Love? Love does not do this. this is hatred. I feel hatred and seek revenge; my adversary is within and I needs must confront him. Even so, there is still in my mind a modicum of sense that is aware of the irony of the situation. I begin from where Mustafa Sa’eed had left off. Yet he at least made a choice, while I have chosen nothing. For a while the disk of the sun remained motionless just above the western horizon, then hurriedly disappeared. The armies of darkness, ever encamped near by, bounded in and occupied the world in an instant. If only I had told her the truth perhaps she would not have acted as she did. I had lost the war because I did not know and did not chose. For a long time I stood in front of the iron door. Now I am on my own: there is no escape, no place of refuge, no safeguard. Outside, my world was a wide one; now it had contracted, had withdrawn upon itself until I myself had become the world, no world existing outside of me. Where, then, were the roots that struck down in times past? Where the memories of death and life? What had happened to the caravan and to the tribe? Where had gone the trilling cries of the women at tens of weddings, where the Nile floodings, and the blowing of the wind summer and winter from north and south? Love? Love does not do this. This is hatred. Here I am, standing in Mustafa Sa’eed’s house in front of the iron door, the door of the rectangular room with the triangular roof and the green windows, the key in my pocket and my adversary inside with, doubtless, a fiendish look of happiness on his face. I am the guardian, the lover, and the adversary.

“I turned the key in the door, which opened without difficulty. I was met by dampness and an odour like that of an old memory. I know this smell: the smell of sandalwood and incense. I felt my way with my finger-tips along the walls and came up against a window pane. I threw open the window and the wooden shutters. I opened a second window and a third, but all that came in from outside was more darkness. I struck a match. The light exploded on my eyes and out of the darkness there emerged a frowning face with pursed lips that I knew but could not place. I moved towards it with hate in my heart. It was my adversary Mustafa Sa’eed. The face grew a neck, the neck two shoulders and a chest, then a trunk and two legs, and I found myself standing face to face with myself. This is not Mustafa Sa’eed – its a picture of me frowning at my face from a mirror…”

It was scenes of the local village I found most enjoyable. The group of old men gathering every day to chat and drink tea together with one old woman who was able to be included in the otherwise male dominated group. The initial story of the protagonist’s train journey through the north of Sudan. But I have to admit I got a bit lost in trying to understand the nuances of the story.

A reviewer of the book wrote: ” A first reading of Tayeb Salih’s Season of Migration to the North can be a bewildering experience. The episodic manner in which the story is laid out means that important information about the characters and their past is left out, thus giving the reader a sense of being lost in a strange country where he has lost his bearings”. This was true for me.

I didn’t mind the book. It’s what I’m looking for in this endeavor – insights into a completely new and unknown world. But I did feel that I perhaps could have benefited from an annotated version of the novel or a literary ‘notes’. If you like the sublime and the poetic, give it a go.